Story and Photos by Samantha Stetzer

Michele Bacquet’s breath slowed as she steadied herself. She carefully recalled an incident involving a customer who didn’t comply with her restaurant’s mask requirements while going to the restroom in December 2020.

According to an Ada County Sheriff’s Department police report, after the customer was asked to leave, a scuffle broke out. Multiple witnesses recalled seeing the customer slap Michele Bacquet. The deputy also indicated that Michele Bacquet punched back afterward. The Ada County prosecutor declined to move forward with the case, but the effects of the incident are far from dropped for Michele.

“It just makes my heart race thinking about it,” Michele Bacquet said. “I have terrible anxiety about someone coming into my home. This is our home; we do live here, figuratively.”

Despite that drama, the restaurant, Bacquet’s French Cuisine Restaurant in Eagle, does feel homey to server Kimberly Hendryx, who said she’s supported by Michele Bacquet and her husband, head chef and co-owner Franck Bacquet. This stint at Bacquet’s is an opportunity for Hendryx, who gained her footing in food service at age 14, to experience a different level of service — one where she feels supported by her bosses.

“I’ve never worked for an employer who empowered us to feel the way we do as far as, ‘You need to respect us. We are here to give you a real dining experience,’” Hendryx explained.

Yet, Hendryx admits working in this industry, no matter who the employer is, hasn’t been easy for the past two years. Likening the experience as “close to a dumpster fire,” Hendryx, other restaurant employees, and their employers are feeling the brunt of the pandemic burnout experienced by many service workers.

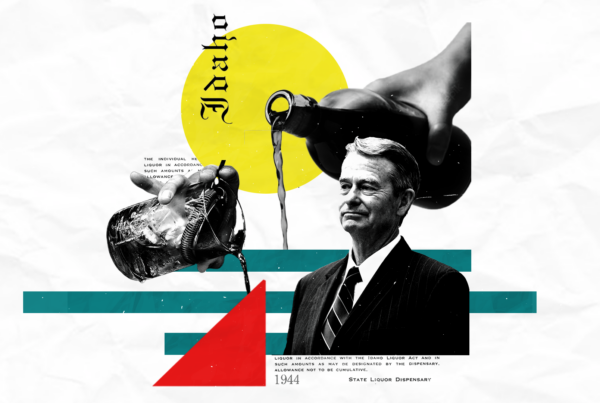

As the “Great Resignation” took off in 2021, the food and service industry saw some of the highest rates of turnover. Furthermore, a February 2021 study of 585 restaurant employees, as published in the “International Journal of Hospitality Management, found those that did stay were more likely to abuse drugs and alcohol and experience psychological distress. (There is a long-time open secret that drugs and alcohol abuse is common in restaurants. A 2009 study found this culture to be prevalent among its young workers.)

To the restaurant owners and employees on the frontlines of cuisine entertainment, there isn’t just one source of the growing burnout and mental exhaustion. It’s a multifaceted “dumpster fire.”

Responsibility in a Shifting Landscape

Michele Bacquet doesn’t take her job lightly. With a military and corporate accounting background, she jumped into restaurant ownership after marrying Franck Bacquet. Living with anxiety even before the pandemic, she explains that owning and operating a restaurant is like putting on her own show; it’s a character she becomes.

For the past two years, that role has been more difficult.

“It’s this deep sense of responsibility for not only the business… the impact not just on the employees, but you got to think of our vendors, our musicians, and our maintenance [crew],” Michele says. “You’d be awake at 2 a.m., worried about how you were going to do tomorrow, and decisions were made in the 2 a.m. hours.”

Louis Aaron, owner of Westside Drive In with two locations in Boise, Idaho, echoed that sentiment. Westside’s team has “had to be creative,” Aaron explained, by cutting back hours, operating with 70% of its staff, and coming this spring, reducing its menu to accommodate food and supply pricing increases.

To make this possible, Aaron relies on his staff, some of whom are teens and young adults in school. However, Aaron explained that many of his staff are also former incarcerated individuals or recovering addicts. They come with their own emotional baggage, and he has witnessed the ways in which the pandemic has made coping much more difficult on his team and those he knows in the industry.

That toll included the death of his best friend, a man who worked for Aaron for 25 years and died after a long battle with alcohol. Because of that battle, Aaron had to make the tough decision to let him go in October 2021 for the sake of the business, he explained. His best friend’s plight isn’t a unique story, either.

“I’ve had a couple other employees leave because of addiction. The COVID-19 thing had been a trigger for them. I think it’s the isolation,” Aaron said. “There’s side effects of that.”

“The COVID-19 thing had been a trigger for them. I think it’s the isolation. There’s side effects of that.”

Those side effects are part of what has weighed heavily on the Bacquets, Michele Bacquet said. They, too, have witnessed employee hardship. She explained they have had to deal with suicide attempts and helping employees find support for their mental well-being. While shouldering that responsibility and for the sake of themselves, their family and friends, and their employees, vendors, and customers, Michele Bacquet said they decided to be as strict as they could be while keeping the lights on. But they struggle with back up.

“We were an island making mask decisions behind that and coming up with protocol on our own,” Michele Bacquet says. “There was just constant push and pull with guests.”

Central District Health (CDH), which provides health guidelines, support, and standards for restaurants in its jurisdiction, including Bacquet’s, provided restaurant owners with pandemic guidelines that followed CDC, OSHA, and National Restaurant Association guidelines. CDH’s Public Information Officer Rachel Garcceau explained these guidelines are not enforced but, rather, are tools restaurant owners in their jurisdiction could use to guide their operations to safely open for dine-in and carry-out meals.

Michele Bacquet conceded that a lack of understanding about the COVID-19 virus contributes to the overwhelming uncertainty, but she expressed feeling as if owners carry most of the weight, while her employees deal with the brunt of the concerns.

For instance, another server at Bacquets, Benjamin Peterson, explained it was tiring to ask “people to put their masks on five or six times.” Idaho has not had a formal statewide mask mandate during the pandemic, though some municipalities and businesses, like the City of Boise and Bacquet’s, have mandated masks.

On top of that exhaustion, servers had major personal concerns of their own.

“In the beginning it was really hard for everyone. It was hard for Michele [Bacquet]. It was hard for me,” Peterson said, later adding, “We have servers that work at multiple restaurants, and they are stressed… Money, hours, constantly not knowing if someone in the staff is going to come in with COVID-19. You just don’t know. It feels like we’re in a constant state of unknown… Am I going to have a job next week?”

Combating a Growing Issue

For the past two years, restaurant workers and owners have had to find their own way of coping. Hendryx approaches every day as a new day. Aaron throws all his concerns up to God — something he also helps his employees who are struggling do. Michele Bacquet helps others by donating meals to locals in need or finding support for her staff, and Peterson challenges himself to turn rude customers into raving fans.

Collectively, the owners and employees have learned that coping with the mental strain of the pandemic meant coming together. Libby Engebrecht is a licensed clinical social worker with Terry Reilly, and she explained this perspective can be critical for employees.

“One of the struggles that [people] experience, and I think a lot of people struggle in other industries as well, is their values versus the values where they work,” Engebrechet said, later adding, “That can be very difficult.”

Engebrecht, who has been with Terry Reilly for 26 years and commonly works with adults who have “severe and persistent… mental illness,” encouraged employees who are struggling with their mental well-being to focus on what they can control: their approach. She suggested workers readily use their breaks to go for a walk or to spend time outside.

“Literally smell the roses and remind your body and yourself that there is a world outside of the walls. Just a step out,” Engebrecht said. “And, again, [remind yourself], ‘I can do this. I am in control of this.”

Owners like Michele Bacquet and Aaron have also offered emotional and mental support to their employees. Aaron and the Westside crew have a mental health specialist they rely on, providing their services to any employee in need of support and care. Michele Bacquet says she has helped current and former employees navigate job applications and supported them through major life transitions.

Peterson, who works part-time at Bacquet’s, explains working for an employer like the Bacquets makes the added stress of managing customer expectations during a pandemic easier.

“Most of the kitchen staff and the front of the house, they know that Franck and Michele [Bacquet] have our back. They have our best interest first,” Peterson said.

This is another crucial component, explained WeVow’s Matt Pipkin. WeVow offers sexual assault response training and resources to staff and employers at food and beverage companies, like restaurants and breweries. Pipkin explained he has found that when employers are engaged with creating a space where their employees feel safe, that message resonates with their employees.

“You have to make sure people understand where you stand,” Pipkin explained.

Businesses who participate in WeVow’s programming also receive counseling resources for those who are assaulted while working. According to Pipkin, the use of the tool is low, but the comfort of its existence is powerful.

“Just knowing that it’s available is a big deal to [employees],” Pipkin said. “Especially in an industry like service, just knowing they have that, it’s a really big deal.”

Beyond sexual assault awareness and resources, there is another form of support restaurant employers can offer their workers, explained Lindsay Clarke Youngwerth, broker and partner with Shandro Group Health Insurance. Recently, Clarke Youngwerth partnered with FARE Idaho, an organization that offers support and resources to Idaho’s independent food and beverage businesses, and the Idaho Manufacturing Alliance to provide Nice Healthcare to employees. The coverage costs just $36 per month and includes services like mobile check-ups, telehealth opportunities, physical therapy, prescription coverage for 550 generic medications, and, as a result of the pandemic, mental health care.

“People equate a career to the benefits they receive from their employer,” Clarke Youngwerth said. “What their intention is with Nice is to take a benefit for those key people [restaurant employees] who show up everyday and create a community within our community. But then also helping them solve other problems.”

Since implementing Nice locally, Clarke Youngwerth has heard about restaurant employers providing telehealth rooms for employees and employees who have received care while working — without disruption. She added that Nice healthcare sees three times as much use as traditional healthcare plans.

All of that equates to a potential solution to the churn of restaurant employees.

“What we want to do is develop this level of care that creates this sticky factor,” Clarke Youngwerth said.

After nearly 30 years of serving customers and working with numerous bosses, Hendryx has seen what works in this industry and what fails. To her, the greatest employers have a “better open door policy.” She added that more restaurants need to improve these policies. She also encouraged restaurants to offer mental health days to provide their employees an opportunity to take a break when they need to. And she encouraged owners to listen.

But it’s not just on the owners who share responsibility, Peterson explained. Good tips are also useful, and Peterson believes 20% just isn’t enough anymore. As prices increase, tips have to, as well.

Michele Bacquet and Aaron encouraged customers to have patience, and Michele Bacquet asked customers to trust that owners know what they are doing to protect their business and consumers.

As for Hendryx, it all starts with a little compassion.

“I think everyone just needs to lead with kindness,” Hendryx said. “Kindness goes so far… we’re all struggling to a certain degree.”

Like others experiencing a pandemic-induced wave of business, Smitten Sweets’ business as of fall 2021 has leveled off, Caleb Smith said, but he’s tapped into a market he believes is strong and has a promising future.

“Just the presentation of having someone with a big smile show up and say ‘Hey, this is something unique and important,’ it’s fun,” Caleb Smith said. “And… that they taste good is after the fact.”

If you need mental health assistance, please contact the National Alliance on Mental Health at NAMIIIdaho.org, or call 208-520-4210. Idaho’s Suicide Prevention and Crisis hotline is 208-398-4357. Call 911 for emergencies.

Samantha Stetzer began her writing career in newsrooms in the Midwest, reporting on various community events, leaders, and news stories. Today, she writes marketing materials for small business leaders and reports on local events, community stories, and food-related news for various publications in the Treasure Valley. For inquiries, please email sstetzer12@gmail.com.