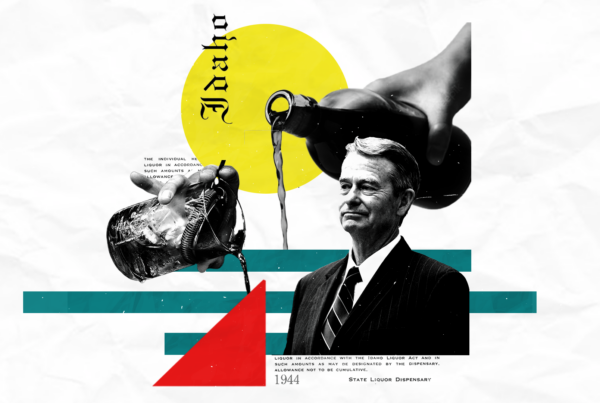

Story by Samantha Stetzer; Photos contributed by Linda Lemmon

Gary Fornshell has a knack for fine-tuning the palates of those who hate seafood into devoted consumers.

His secret is not so well kept, Fornshell jokes. It’s Italian dressing as a marinade, a little paprika sprinkled on top as the fish grills, and for the main event: fresh skin-on Idaho-raised rainbow trout.

Fornshell, the University of Idaho Extension’s recently retired aquaculture educator of nearly 30 years, is just one of the many advocates and researchers within Idaho’s aquaculture operations, which are largely condensed along the Snake River in the Magic Valley. The U.S. Trout Farmers Association estimates that 75% of the nation’s consumed trout is raised in Idaho, largely due to the natural springs that comprise Idaho’s middle-south region.

Growers, breeders, and processors like Linda Lemmon of Blind Canyon Aquaranch and Idaho Springs Foods and Leo Ray of Fish Breeders of Idaho are part of the patchwork of aquafarmers in Idaho who are growing and producing trout, sturgeon, tilapia, catfish, and their caviar, among other varieties.

As COVID-19 continues to wreak havoc on the nation’s economy and well-being, fish farmers have had to face a slew of new issues, on top of environmental standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality (IDEQ), who have been closely monitoring fish operations for years.

These concerns combined with a growing fear that the American consumer doesn’t eat enough fish, have meant that Idaho’s quiet but mighty fish operations are filled with farmers who have learned one thing over the years: Adapt, or dry up.

COVID-19, American Consumption Threatens Idaho Trout

The COVID-19 pandemic brought the global economy to its knees this spring, and perhaps no industry felt this as hard as the restaurant business. But in Idaho, the aquaculture sector was also hurting.

“It’s really been devastating to the industry,” Ray said. “Probably no single industry dependent on the restaurant industry as [much as] seafood. You eat beef and steak at home, and then fish, most of the time it’s eaten in restaurants.”

With dwindling demand, the supply that fish farms are producing has decreased. At least one processing plant in Magic Valley has temporarily closed due to COVID-19, Lemmon said.

The trucking and shipping industry, Ray added, has taken a serious hit, too, as there are less fish orders to haul.

Shipping fish already comes with its own challenges, both Ray and Lemmon explained. Fish has about 48 hours from the time it’s harvested to the time it’s on a consumer’s plate or flash frozen. This ensures the meat is safe to consume.

In a non-pandemic-riddled year, Americans also struggle to consume the recommended dietary guidelines of seafood. The USDA estimates that the average American typically eats about 16 pounds of seafood in a year — an average that was on a steady rise but is still about 10 pounds under the recommendation for a healthy diet.

Lemmon said she believes that many people are so accustomed to pork, beef, and chicken that they may not even realize how easy, efficient, and healthy fish can be.

“A year ago, I would have said fish farming is going to be here forever, but with COVID right now and people changing what they want to eat and how and where, that’s going to affect the industry,” Lemmon said. “The U.S. consumer doesn’t want to cook a lot of seafood by themselves. They want it cooked for them.”

Finding Sustainability in a Changing Industry

Lemmon jokes that there’s only one reason why she became a trout farmer: “I married a trout farmer,” she said with a laugh.

In reality, Lemmon’s career in the Idaho fish farming industry has much more to do with her research and fascination for aquaculture than it does a meet-cute. Her story of adapting to her industry and finding solutions to aquaculture’s hurdles is a common theme for many aquaranchers.

Likewise, Ray learned quickly that he had to change to a transforming landscape. He grew from a catfish-only operation and added trout, tilapia, and sturgeon. He claims to have also become the first known land tilapia farmer in the U.S. in the mid-1970s.

Meanwhile, Lemmon began her career studying shrimp larvae for the University of Texas A&M. When a feed company Idaho wanted to manufacture a new feed, Texas A&M loaned Lemmon and her expertise to the company for two years. After one year, Lemmon fell in love with the industry and a trout farmer, Gary Lemmon.

Today, their family-operated aquaranch owns four farms, leases seven others across Magic Valley, and harvests sturgeon and trout for meat and sturgeon caviar, too. The ranch also operates Idaho Springs Foods, a processing plant where caviar and fish meat are processed and packaged for sale to restaurants and distributors across the U.S.

The Lemmons and Ray’s operation have made some of the biggest “splashes” in the Idaho fish farming and processing industry, but it’s the work they and other aquafarmers in Idaho have had to do on the sustainability front that has been of the biggest concern for environmental groups.

In 1986, Blind Canyon joined Fish Breeders of Idaho, the Idaho Aquaculture Association — of which Lemmon is the acting executive secretary — Idaho Fish & Game, College of Southern Idaho, and others to protect and repopulate the Idaho White Sturgeon. The bottom-feeding, shark-like species is the largest fish in North America but was bordering extinction due to overfishing and dam construction.

The Idaho White Sturgeon Cooperative sought to protect wild sturgeon populations while aquaranchers produced sustainable fishing operations to repopulate the species in residential settings.

Wild white sturgeon must be caught on a catch-and-release basis today, but its residential growth rate continues to rise.

But it’s not so much the fish that have been under the microscope from environmental groups as it is the water that flows around them.

As Jonathan Oppenheimer, Idaho Conservation League’s external relations director, explains, the Snake River has been a major concern for state and federal conservation groups for decades.

The river begins in western Yellowstone and “snakes” its way along the bottom of Idaho to Brownlee Reservoir. The headwaters of the river is world-renowned for its pristine, cold waters, where – of all things – trophy-winning trout have been caught.

Brownlee knows a very different Snake River.

Oppenheimer, who also serves as the director of the league’s Snake River Campaign, explains that it isn’t uncommon for officials to make yearly warnings against swimming out of the Snake River in Brownlee. Along the way, the very same river that is known for its pure qualities turns into dangerous sludge that has hurt humans and killed pets and livestock.

“When you have a river that you can’t touch, there’s something going on, and something that needs to be fixed,” Oppenheimer said.

Phosphorus and nitrates are among the major contaminants along the Snake River, but as Oppenheimer explained, not all sources of the pollutants are tracked or regulated. This includes farm run-offs from feedlots or fields. Flow coming directly out of power plants and aquaculture ponds are regulated, but other run-offs, Oppenheimer explained, are not as easily trackable and therefore have more voluntary requirements.

To solve this, aquaculture and agriculture representatives, processors, and conservationists have teamed up to create the Middlesnake Watershed Advisory Group. The goal is to ensure the load of pollutants dumped into the Snake River isn’t too much for the flow of the river, Oppenheimer explained.

Fornshell believes there have been significant improvements and changes in the aquaculture community alone, starting with farms’ flow systems. These push the water between the pools and the natural springs of the Magic Valley. Filtration systems are designed to catch irritants that mostly come from fish excrement before it populates the natural spring waters, but not all the contaminants are captured.

Fornshell explained that researchers recognized the need to limit waste and excess feed, and they did so by determining how much food fish, trout specifically, actually need. Researchers determined the ratio is about one pound of feed for every one pound of trout.

Next came the composition of the feed.

Previously, most fish food would fall to the bottom of the pool. However, for trout and many other species that feed from the top of the water, this meant more food was going to waste. (That was great for Sturgeon, who are bottom feeders.)

A change in composition to create extruded pellets allowed the feed to float or sink slowly, which allows top-feeders, like trout, to consume the proper amount of feed, excrete less waste, and leave less feed at the bottom.

The result of this work, explained Fornshell, is that the aquaculture community has decreased its phosphorus contaminants by 49%, and today, aquaculture contributes to about 16% of the phosphorus waste in the Snake River.

However, that and other actions are just the beginning of what needs to happen on the Snake, Oppenheimer said, adding that the work done today likely won’t make a real impact for generations.

“The challenges in the Snake are really significant,” Oppenheimer said. “It’s going to take a commitment from the state and federal governments for the Snake… Develop some programs that can support agriculture, can support aquaculture, can support the communities, but provide some investments to address the pollutants that are leading to some of these unacceptable conditions.”

As generational shifts and a continued focus on sustainability grows, Lemmon, Ray, and Fornshell are optimistic about the future of the fish farming sector of the Idaho agriculture landscape – despite all the challenges that come with it.

“Raising fish is just like raising cows and pigs and chickens,” Ray said. “You gotta feed them, you gotta clean up after them, you gotta move them. It’s just different methods of doing that, but it’s just farming like it is raising any other animal.”