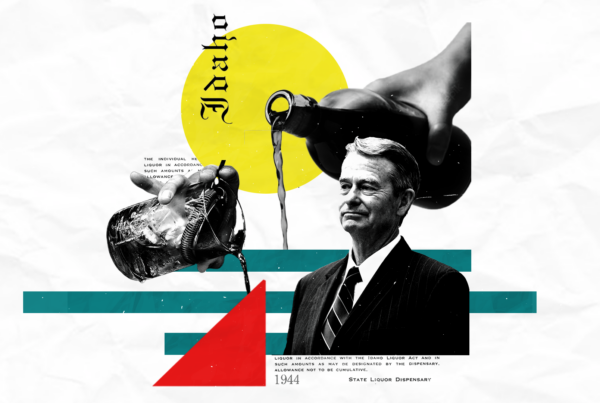

By Carissa Wolf; Illustrations by Felicia Weston

A patron’s wheelchair gets stuck in a Boise bar bathroom that appears accessible but isn’t. Other patrons pry said guest’s chair (along with their very full bladder) free from the clinch of bathroom stall doors.

A birthday party guest with mobility impairments circles the downtown Boise core again and again, looking for a place to park within 500 feet of the restaurant hosting the party. After 30 minutes, the parking spots within proximity remained occupied by able bodied customers and the would-be guest goes home.

Patrons see a sign outside a popular Boise breakfast joint that tells customers with disabilities to ring a bell for access. They ring the bell, only to be greeted with an offer to have the strongest employee attempt to carry them up the stairs.

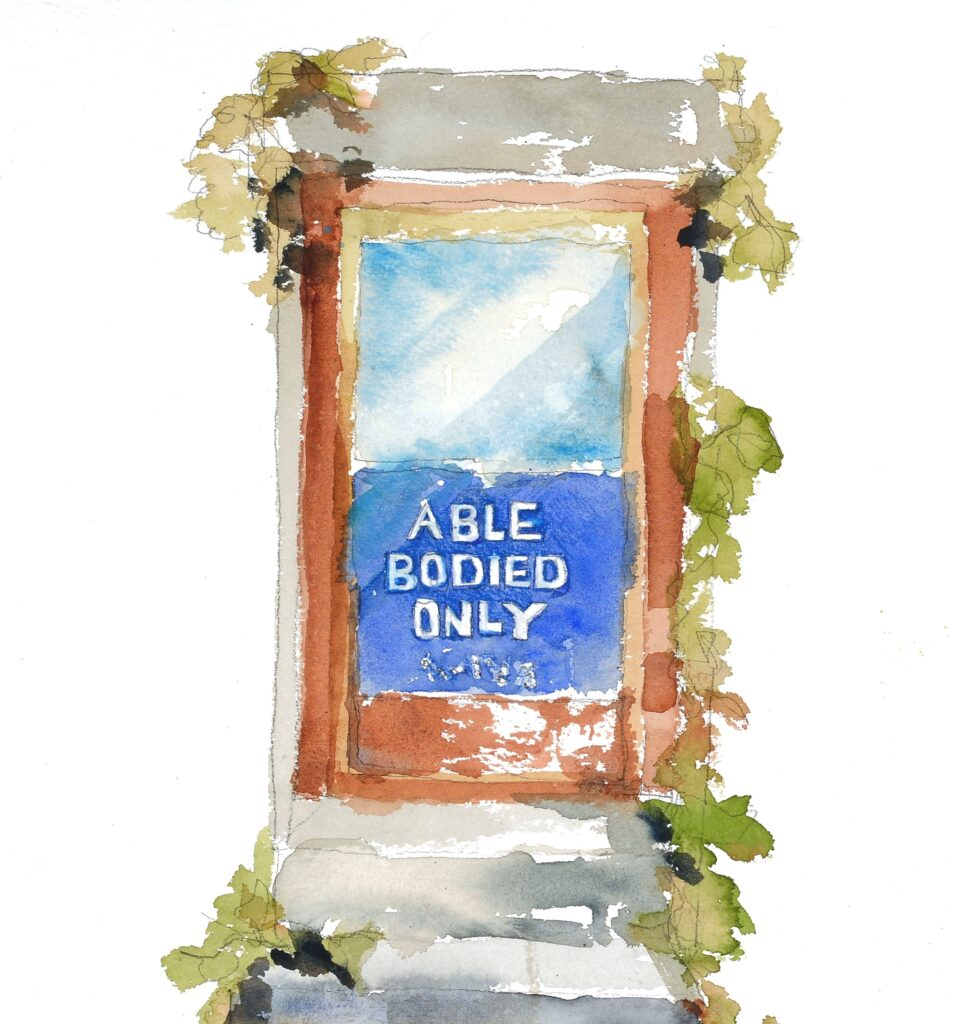

These kinds of situations don’t make headlines and for the people who experience the actual events, they’re hardly a newsworthy moment. They’re just another barrier among the many that accompany the invisible signs that sometimes only they can see.

“ABLE BODIES ONLY,” the signs say.

The signs dot the downtown Boise landscape and sprinkle into the town’s suburbs and countryside. They hang on the front doors of bars, under the menu boards at restaurants and across bathroom stalls. Sometimes they’re written in bold letters in multiple places at culinary hot spots and other times, they appear in tiny font at the bottom of a wine list. The signs all have one thing in common: they’re everywhere. And unless you see the world through the lenses of disability, the signs remain blissfully invisible.

“Once you see the signs, you can’t unsee them,” says retiree, Michele Romeo, a long-time civil rights activist who counts eating among her many beloved abilities.

Getting a seat at the table to do one of the things she says she does quite well is a whole other matter.

“I’ve always felt that everyone should be included in everything,” says Romeo, who counts civil rights champions among her mentors and fought for equality long before equal rights became the law of the land.

When it comes to eating out though, she’s found that laws only go so far.

“Thirty years after (disability rights) became civil rights, I’m still excluded,” Romeo says.

And as a 40-year Multiple Sclerosis warrior, Romeo has also used the gamut of mobility aids. She’s also got a perspective that the roughly 85 percent of people with disabilities who acquire their disabilities later in life see: the signs that were once invisible and the treatment that accompanies that signage.

“People treated me so differently as a non-disabled person,” she says.

Romeo’s experiences with a disability at Treasure Valley restaurants could fill a book with harrowing and heartbreaking stories. The specifics and details of her fight to get a seat at local tables might look a little different from the 20 percent of the population with a disability, but the storyline comes with the same access denied ending after seeing that same invisible sign on the front doors of bars and restaurants: “ABLE BODIES ONLY”.

“If there was a sign that said, ‘Whites Only,” you bet (owners),” would take it off,” Romeo says.

While the Covid-19 pandemic shuttered restaurants, kept people at home and made take-out the only dining option, people with disabilities across the nation felt a sense of familiarity and for once, a sense of inclusion. For the first time, restaurant options looked the same for them as it did for everyone else: sans drive-throughs, deliveries and curb-side pick-up, there were no options.

“All of us have gotten the chance to experience social exclusion. But people with disabilities are saying, ‘This is how I experience life all of the time,’” Romeo says.

The fixes to that exclusion are often so simple and don’t cost a thing; moving a table to widen a pathway, ensuring that bars have a variety of table heights, removing chairs, unfolding a simple and inexpensive ramp, uploading menus online in non-pdf formats (so a phone app can read the text), marking barriers with contrasting colors…

The list goes on.

“’I’ve always felt that everyone

should be included in everything,’

says Romeo.”

Romeo and others with disabilities find that attempts to expand their options are often met with hostility, indifference, insensitivity and heartbreaking acts of ableism. Those attempts often come with a simple request: to move a chair, place a ramp over a step or bring a lower table into the room. She found some establishment owners and employees battle the simplest and cost-free requests for accessibility, forcing customers to file complaints and battle accessibility out in courts. On a recent encounter, an employee kept referring to people with disabilities as “those people,” and “them.” At a winery on a pre-pandemic day, Romeo’s request to sit at an accessible table during a group event left her sitting at the far end of the establishment, segregated from the people she came to enjoy the evening with.

Others comply. And a few – Romero can count the establishments from Boise to Eagle on one hand – go above and beyond at establishing an accessible food and beverage environment.

“This is like needing a modern-day Green Book,” Romero says. “From my perspective, this isn’t charity that you’re doing, this is equal access under civil rights law,” she says.

The 1960s and 1970s brought an era of civil rights activism into the forefront and disability advocates saw it as an opportunity to join with other underrepresented forces to build a more equitable society. The activism pushed legislation into law that challenged the reigning Medical Model of Disability that saw disability as impairment of the individual that limited participation in society and shifted focus to a Social Model of Disability that saw barriers as social in nature. These barriers were seen as surmountable with attitude changes and renewed attention to the ways that we can build and shape our communities to create a more accessible world. But the United States saw pushback from businesses that blocked comprehensive disability rights legislation for nearly two decades. Their main beef: accessibility mandates would be too expensive.

“’All of us have gotten the chance

to experience social exclusion.

But people with disabilities are

saying, ‘This is how I experience

life all of the time,’” Romeo says.”

The sentiment didn’t jive with public attitudes.

A year after the eventual passage of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act, a Lou Harris poll found that 98% of polled individuals believed that people, regardless of ability, should have the opportunity to participate in mainstream society.

The ADA ushered in a host of provisions that aimed to eliminate the social barriers that turn impairments into disabilities but the law, which is largely enforced through complaints, carries a host of exemptions that leave the hope behind the law an unfinished dream.

The law exempts some businesses from mandates to provide accessible public spaces because of the age of a building, the number of workers employed, or simple infeasibility, leaving the creation of an accessible place up to the business. While many businesses work with accessibility consultants to ensure that their facilities are accessible to the public, people with disabilities find that for many restaurants, especially small, independent establishments—the kinds of business that are often exempt from some ADA provisions—accessibility is an afterthought or not even thought of at all. And accessibility advocates say it’s that afterthought, or business as usual attitude, that makes ableism systemic, segregates and keeps scores of would-be paying patrons from having a seat at the table.

‘The sad thing is, I know good food,” Romeo says.

Accessibility requirements can vary from municipality to municipality, access can vary from neighborhood to neighborhood and it’s often up to businesses to decide how accessible they want to make their establishment. That’s why a wheelchair user can get stuck in a Boise Bench bar restroom that appears accessible but actually isn’t, but that same person could easily traverse San Diego streets lined with trendy restaurants and know exactly how accessible an establishment is before setting foot into the place to find out (and getting stuck in the process). Outside those San Diego eateries, square blue accessibility signage prominently signals to users which restaurants are accessible and which ones are not.

Boise still lacks those kinds of accessibility guides. And they can go a long way in taking the embarrassment, anxiety and wasted time out of pursuing a meal that may or may not be accessible.

Laine Amoureaux, who owns the accessibility consulting firm, Amoureaux AT Consulting in Boise, sometimes thinks back to her days of dating with a disability. The already nerve wracking first date was often made even more nerve wracking by walking into a restaurant and not knowing how accessible the establishment would be for vision impaired patrons. Would steps and other barriers be clearly marked with contrast? Would there be menus in Braille or at least digital copies she could access online in non-pdf formats? What if they changed the menu she already memorized? Would her date have to read the menu to her? Would the server ignore her, as they often did, and ask her date what she wanted to eat for dinner?

“I never wanted someone I was dating to feel like they were taking care of me,” she says.

Low-cost awareness and accommodations could solve many of the barriers that Romeo and Amoureaux encounter. Disability advocacy groups such as the Independent Living Network and Northwest ADA Center offer resources and training on the ADA and accessibility. Other places like the Idaho Commission for the Blind can assist in crafting accessible aids, such as printing Braille menus. And independent consultants like Amoureaux can help business craft budget-friendly accessibility plans.

Thoughtful planning and awareness can help remove those signs, advocates say. And an accessible menu can help make someone’s first date a little less anxiety ridden.

Amoureaux says, “It’s just one less thing I have to worry about when I get there.”