Story by Guy Hand

Much that is wrong with modern agriculture begins with a seemingly innocuous, if wonky phrase: The principle of comparative advantage.

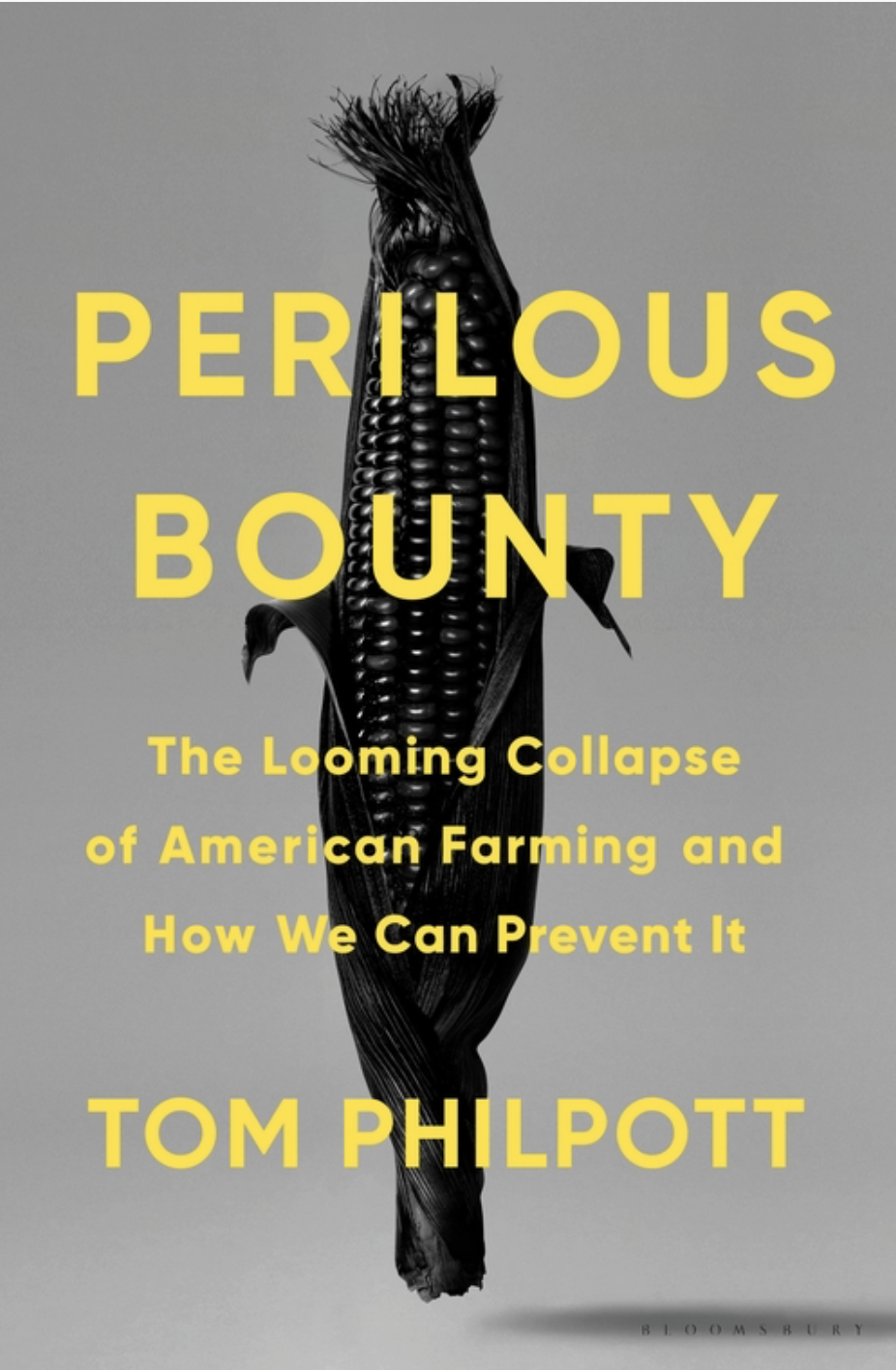

According to Tom Philpott in his important new book Perilous Bounty, this nineteenth-century principle evolved from a general economic theory to one that urged every region across the globe to specialize in growing only those crops that each climate and soil type is best suited to, then growing lots of them and trading the surplus for the bounty of other regions.

The logic seems irrefutable: we trade cool-region apples for warm-region oranges, dry-land beef for oceanic tuna. The principle so dominates modern agriculture it seems as inevitable as gravity. But Philpott argues this high-volume/single-crop-approach is also destroying the best farm lands on the planet—and therefore, humanity’s ability to feed itself.

To illustrate his point, Philpott explores two of America’s most productive farming regions: California’s Central Valley and the Midwest’s corn belt. Yet the problems he witnesses are translatable to any region that specializes in agricultural products grown in vast quantities for national and international trade. Think the potato fields of eastern Idaho, the factory dairies of the Magic Valley or the wheat fields of North Idaho and Eastern Washington.

The principle of comparative advantage was first formulated by David Ricardo, an English economist who lived from 1772 to 1823, exactly when the Industrial Revolution was transforming largely rural, agrarian England into an industrialized, urban powerhouse. Goods that for centuries had been crafted by artisans were quickly replaced by unimaginable amounts of inexpensive products pumped out by newly built factories. From this perspective, Ricardo believed specialization combined with free trade would always produce positive results. It was only later, most significantly after World War II, that his principle of comparative advantage moved decisively from factory floor to farm field.

“The principle so dominates

modern agriculture it

seems as inevitable as gravity.”

But what that nineteenth-century economist could not have foreseen hidden behind the logic of his own theory were the devastating environmental, cultural and economic realities writer Philpott encountered while touring the industrial farms of California and Iowa.

“In this book,” Philpott writes, “I’ll show how this apparent triumph of comparative advantage is like the sight of water in a sunbaked desert: a mirage, and a dangerous one for U.S. eaters.”

Rather than dwelling on economic theory, Philpott walks the almond orchards of the Central Valley, which, at over a million acres and growing, cover a fifth of the farmland in the San Joaquin Valley and consume four times the amount of water used by Los Angeles. (So much groundwater is being sucked from the aquifer by agriculture that the valley floor is sinking ten inches a year.) In Iowa, he drives through endless monocultures of soy and corn, “two species, packed as close together as city commuters on a subway at rush hour” and factory hog farms that emit “an overwhelming putrid stench that triggers a flight response.” Jacked up on pesticides and synthetic fertilizers, the two regions are depleting their water and soil resources at an alarming, unsustainable rate that, Philpott warns, climate change will only accelerate.

Still, he doesn’t blame farmers for the excesses of an economic theory hatched by a Londoner over two-hundred-years ago. After all, those farmers are trapped in a system where the more product they produce the lower prices fall, requiring them to plant more to compensate, which lowers prices further. The only way many farmers escape that downward spiral, according to Philpott, is by harvesting the billions of dollars of annual supports provided by the government.

The true beneficiaries of Ricardo’s theory are agricultural corporations.

“What drives this creeping disaster,” Philpott writes, “is the rise of a virtual oligarch of companies that capture most of the profit generated by the trillion-dollar-a-year food economy.”

It starts with the near monopolistic control of big ag. by companies like John Deere, which sells 63% of all the massive combines required by large-scale farming sold in the U.S., to four companies that control the $11 billion American fertilizer market, to three companies that control the seed and pesticide market, to another three grain traders and meatpackers.

“Jacked up on pesticides

and fertilizers, the two regions

are depleting resources

at an alarming rate.”

To maintain their power, this handful of companies spend around $100 million in campaign contributions every federal election cycle and billions on lobbyists while simultaneously mining soil, water and human resources to manufacture food that Philpott writes “leaves a pandemic of diabetes, obesity, and heart disease in its wake.”

So, where’s the hope in all this agricultural gloom?

Philpott says it comes in dispelling the myth of comparative advantage, what he also calls “the great simplification.” We now know what nineteenth-century economist David Ricardo did not: that biodiversity is key to environmental health and that the simplification of vast landscapes, like the fence-row-to-fence-row monocultures of industrial agriculture, is the enemy of both human and environmental health. Rather than concentrating production of specific crops in single areas, Philpott says “It’s time to mix them up and spread them out.”

In the Midwest, that means broadening the crop mix beyond corn and soybeans, and moving animals from feedlots and confinement facilities and back on the land. For California, that will mean a scaling back of agriculture to fit the state’s changing water resources.”

For those of us who live outside those two “breadbaskets” of production, it means becoming more self-reliant by re-localizing and regionalizing food production. If that sounds a lot like what the local food movement is already doing, Philpott agrees that “the dramatic buildup in local food that has taken place in the twenty-first century is a priceless asset,” but he also says that going to farmers markets, joining CSAs and “voting with our forks” is not enough. Big ag. is simply too big. It has too much influence over state and federal policies, not to mention international trade laws that push decentralized, diverse forms of farming to the fringes worldwide.

Proponents of industrial farming counter that alternatives are inefficient, elitist and therefore deserve the fringes. But Philpott points to studies where conservation practices like no-till farming, cover-cropping and crop diversification have actually increased production while saving farmers significant money by limiting the need for expensive, environmentally-problematic inputs like synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

“Rather than concentrating

production of specific crops

in single areas, It’s time to

mix them up and spread them out.”

Philpott also addresses the need for local agriculture to include not only the popular direct-to-consumer, farmers market and CSA model, but also a medium-scale model that could supply higher volumes of local food to schools, hospitals and far more independent restaurants than is currently possible—while still avoiding the excesses of highly-consolidated commodity and export markets by keeping their reach regional.

‘Finding economic models that allow midsize producers to thrive is crucial to the needed transformation of our food system,’ writes Philpott.

But to transform anything, he believes we have to also break the grip industrial agriculture and the flawed principle of comparative advantage have on the current system. To do that, Philpott writes, we also need to make changes at the top of the political food chain. We need a president who believes in the science behind climate change and biodiversity and politicians who aren’t tied to big ag. money and the influence of big ag. lobbyists. It means not only considering what makes cash for large corporations, but what makes sense for farmers, farmworkers, consumers—and the planet that feeds us all.