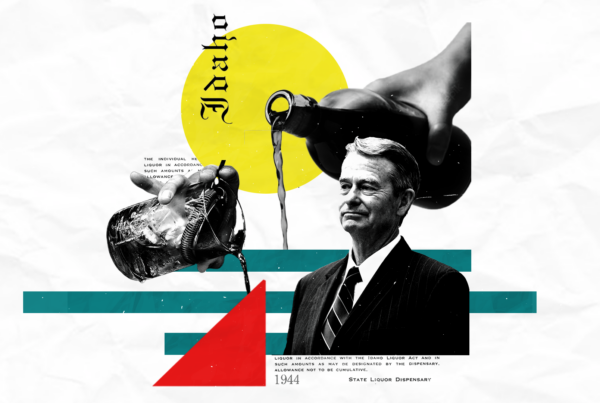

Story by Courtnie Dawson

(featured photo by Matthew Wordell)

Barleywine debuted rather recently in beer history, but with hazy IPAs and candy-themed ales taking center stage, this dark, boozy beverage is shrouded in mystery, a novelty found in the occasional taphouse, but rarely seen in supermarkets or bars. But if you’re brave enough to order that single barleywine on the menu, chances are you’ll be shocked and delighted by one of the most intense, complex, beer experiences of your drinking career.

Barleywine first earned recognition in 1870s England. Pragmatic English brewers would use massive amounts of malt and hops to create several batches of beers from a single mash. The first batch would be strongest in flavor and alcohol content, making them the best contenders for storage in barrels. The following batches would grow lighter and lighter, and have to be consumed more quickly. The barrel-stored took on characteristics of the wood as they aged, building a mosaic of flavor into an already hefty brew. The style gained momentum with America’s craft brewing movement in the 1970s, with Anchor Brewing toting the first commercially-produced “barleywine” beer.

The name “barleywine” has nothing to do with grapes or vines. The name is merely a nod to the beer’s traditionally high alcohol content and flavor complexity. In the early to mid 1900s, most beers fell between 4 and 5% ABV, while barleywines rocked the palate at 8% and above. For brewers to reach that considerable level today, they require nearly double the malt for enough sugar to be converted into double-digit ABVs. All that malt creates a syrup-sweet brew that needs to be tempered. Hefty amounts of hops are then used to counter that overpowering sweetness. The combination of so many ingredients results in robust, vivid flavors that dominate the palate. There’s a thin line to be traversed in order to make that experience enjoyable, and the key to walking it is balance.

Despite their long history, fascinating flavor profiles, and an ABV that would put hair on anyone’s chest, barleywines are not a common find anymore. In an age of IPAs and light beers, these bottles have taken a backseat, even in the Treasure Valley craft brewing scene.

“It’s not a popular style commercially at all,” says Lance Chavez, head brewer of Boise Brewing. Lance crafted their first and only barleywine, “Brewtus”, in 2016. “They’re sipping beers, so you aren’t going to sell three pints in a sitting like you would an IPA or pale ale.”

So why do brewers consider a beer that takes double the resources and makes less profit? Because they want to.

“It’s a brewer’s favorite,” Lance says.

For some, it’s the novelty of brewing a more obscure beer. For others, it’s a matter of taste and preference. And for many brewers, it’s about tribute to those that have gone before.

Regardless of motivation, at the heart of barleywine brewing there are two common styles: English and American.

The original English-style of barleywine tends to favor more intricate malt characteristics, and gentler English hops with less bitterness or citrus. Considered to be more well-rounded in flavor, they maintain a good balance between boozy, malty, and hoppy; no single characteristic outweighing the rest. English-style barleywines convey flavors of dark fruit, caramel, toffee, and molasses.

As a fan of dark beer, this style is where brewer Tyler Evans shines.

“I really enjoy the complexity of the malt characteristics,” says Tyler, head brewer at Powderhaus Brewing.

“Double Deadfall Ale” came out of the starting gate with Powderhaus’s inception. With their reputation for darker, heavier beers, a “winter warmer” made perfect sense in the context of a ski-themed taproom and passionate malt-loving brew team. The barleywine, available in house and as one of the very few Boise barleywines distributed outside the taproom, stands defiant against a massive consumer pressure towards beers light enough to see through.

“I’ve made lots of big beers. Russian Imperial Stouts, barleywines, etcetera, as a homebrewer,” says Tyler. “Those are beers you couldn’t get very often, but you could get light beers anywhere. I tend not to make those light beers as much.”

Meanwhile, the American-style barleywine, the rebellious younger brother of English-style, is known for packing in significantly stronger, West-Coast hops; the higher the alpha oils, the better. Where malts provide the target flavors for an English-style, the American-style barleywine is all about showcasing an intense hop bouquet. The Western American hops assist in this goal, with their higher alpha oils, more dynamic pine and citrus notes, and juicier bitterness.

“With an American-style, you’re naturally getting that bittering balance from the hops and malt, but also getting the heat from the alcohol,” Tyson Cardon of Sockeye Brewing says. “It’s definitely a sipping beer, but it has that balance.”

Sockeye Brewing has been making “Old Devil’s Tooth” Barleywine for nearly two decades. In 2002, the brewers sought to create a beer with a legacy: something to showcase a good balance of hops and malt that would hold up well for aging, and could be compared year after year as the recipe was tweaked. With twenty years under its belt, the Sockeye team has solidified its understanding of barleywine.

“American-style barleywines tend to be almost like an intense IPA, which is what we had originally planned to make,” Tyson says. “But we wanted something hoppy that also had a strong malt backbone. “[Old Devil’s Tooth] was born from the desire to make a big beer.”

It’s no surprise that some Boise breweries would drift toward American-style, with Idaho being the 2nd top producer in the country for hops, with some of the highest quality varieties grown mere miles away. American-style barleywines are the perfect opportunity to showcase that Western-American intensity.

“Without those hops, [barleywine] would be an insanely sweet, fruity beer with no depth or characteristics,” Tyson says. “But if you have a good balance of hops, alcohol flavor, and sweet mouthfeel, then you have a good barleywine. Those hops are the key to that balance.”

Then there are those who want to have it all: tradition, creativity, English, American, malt, hops. James Long, co-owner and head brewer of Barbarian Brewing, stands on both sides of the fence, with two opposing barleywines in his line-up.

For Barbarian Brewing, which is known for a colorful variety of beers that float between barrel-aged stouts and crazy candy-inspired ales, barleywine doesn’t stand out as exotic, compared to items like “Blueberry Cheesecake Stout” and “Strawberry Meringue Sour.” But what makes their Stormbringer barleywine a surprise on their menu is that it is based on tradition rather than their usual break-the-mold approach.

“We do make a lot of crazy beers, but we made [Stormbringer] because barleywine is a traditional style,” says James. “I have a special place in my heart for tradition, for beers that have been made for hundreds of years.”

Not to say that a beer so rooted in tradition lacks room for innovation. Most of Boise’s barleywine brewers have played with their beer, such as adding fruit (Barbarian’s English-style “Dutch Apple Streusel”), aging in different kinds of barrels (Powderhaus’s “Old Fashioned”), and even mixing with other beers (Sockeye’s “Old 7 Tooth”).

“We like to make a super traditional style, but also like to have fun with it,” James says.

Even in the small niche of Boise-based barleywines, no two are alike. Just as the beer’s recipe requires balance, so too does the tightrope of tradition and creativity that makes these barleywines shine.

“[Making barleywine] has meant doing a lot of research,” James says. “Picking apart recipes I’ve tried commercially, then translating them to our beers and putting our twist on things. Most importantly, it’s about finding the best quality ingredients and going from there.”