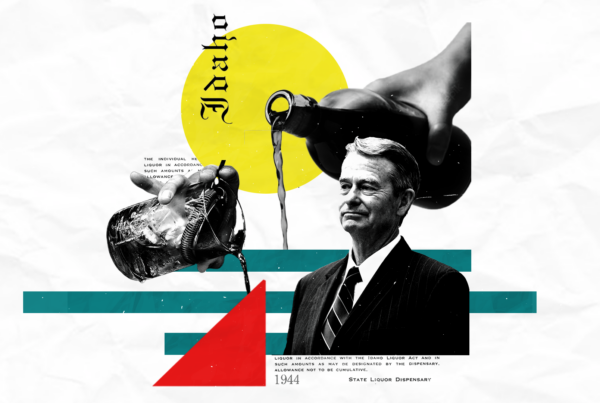

Story by Samantha Stetzer; Photography by Guy Hand

Whether it’s a lesson we learn when our moms shuffle dollar bills into our palms for the hair dresser, or our parents’ Friday night debates over how much to leave the waiter, every U.S. citizen learns how to tip. It’s the way Americans “reward” service workers for their due diligence, and today, many of those who receive tips enjoy their jobs.

“The hours are flexible, and you’re able to make a decent wage in a short amount of time,” said Crystal, a former server who asked that she was identified by her first name only. “I traveled a lot in my 20s, and I was able to work half a year in a restaurant and travel the world the rest of the year.”

Emma Fullmer, another former Boise-area server, agreed.

“The tips were actually pretty good. It was nice to have that money in pocket,” Fullmer said. “I enjoyed working with people.”

The same also goes for Kelsey Jae, who often enjoyed the back-and-forth of bartending and dressing up for the evening during her multiple stints at various local bars, and Megan Harrigfeld, who enjoys learning more about her community from her various bar guests.

However, reports by the U.S. Census Bureau of Labor and Statistics have found there are major inequalities in tipping protocol. For example, a 2008 Cornell University study found that white servers typically make more per hour in tips than Latino, Asian or Black servers, and a 2015 study by Restaurant Opportunities Center United found that the disparity widens in fine dining restaurants.

When it comes to the problematic nature of tipping, restaurant servers claim one of the more unchallenged components of the system is that sexual assault and harassment are “part of the job” and the wage they earn.

As a veteran server of 17 years, Crystal has worked in six states along each coast in the U.S., including Boise for a number of years. The harassment dynamic of tipping, she said, is universal.

“It’s a stereotype for a reason,” she continued. “The sexism and misogyny is mirrored and increased in tipping culture. There’s this power dynamic that makes these issues that are already problematic even worse. [It] makes people feel like they have agency over us.”

In states where a minimum tipping wage is legal, the need for tips increase. In Idaho, tipped employees can be paid a minimum of $3.25 per hour. If the state’s standard minimum amount—$7.25 per hour—is not met for hours worked, employers must make up the difference.

Subminimum wage laws further the dangerous components and origins of tipping, argued Harrigfeld. America’s tipping culture originated from Europe, and many experts believe it was used as a loop hole for paying freed slaves very low wages because their white patrons could tip Black service workers the difference – if the patrons believed they earned it.

In an industry now dominated by women, subminimum wage continues in many states.

“Tipping needs to go away. It just does,” Harrigfeld said. “A subminimum wage doesn’t make any sense… You make good money in the service industry, but you’re making money because of a performance.”

For local servers and bartenders, that “performance” has meant brushing off comments about their smiles and hair, eye-rolling at phone numbers left in place of the tip, giving hugs to customers for fear of retaliation, and in some cases, continuing to serve after patrons grab them – like last year, when a man grabbed Crystal’s arm, demanded to see her tattoos and waved a $20 bill in her face when she refused. After nearly two decades, Crystal said she has learned how to set boundaries.

“Over the years, you just get numb to it,” Crystal said. “As women, we face these things more subtlety, of course, in whatever profession we do. It’s more overt [in serving] and it almost felt easier to handle once I was older and got thicker skin and wouldn’t let it ruin my night . . . It gets easier.”

It’s not always easy to say no, said Fullmer and Harrigfeld. In states with subminimum wage, their livelihoods depend on tips.

“If someone treats you poorly and they’re a customer, you just have to take it,” Fullmer said. “You don’t risk putting a paycheck on the line… I felt like I couldn’t speak up because I couldn’t lose a paycheck.”

Chris Davis, communications manager with the Women’s and Children’s Alliance in Boise for the past seven years and a former server herself, explained that comments and actions like the ones many servers have experienced is problematic.

“Commenting on your server and their physical attributes, people would not recognize it, but that is sexual harassment… day-to-day in any other business, it is not acceptable,” Davis said. “That’s the job… You’re not just selling the product; you’re selling yourself. By definition that’s coercion. When looking at consent, that’s taking the consent part away.”

Local servers and experts did have advice for the restaurant owners and patrons who see inappropriate behavior: Speak up.

“You have to give the staff agency,” Crystal said, “and trust them that they understand the situations that they are in and that they have the right to stick up for themselves.”

Jae, who is now an attorney, said she’s known managers who have kicked out patrons for their inappropriate behavior, while others stuck behind the customer. She always felt safe in the establishments that backed her up.

“The situations that were the best for me was when I knew that the bar managers or the owners didn’t think that we had to tolerate it,” Jae said. “I knew that they had my back.”

Fullmer also encouraged patrons to tip at least 20%. To the public’s credit, the BBC reports that more Americans are tipping better and more frequently during the COVID-19 pandemic. Restaurants are responding, too. New York restaurateur Danny Meyer, once known for reversing the tipping model and paying his staff flat wages, has gone back to tipping to help his staff with the uncertainty of the pandemic.

Jae also believes tipping can be great – when it’s consensual.

“I think it really comes down to consent and intention,” Jae said, later adding, “Tipping culture isn’t inherently bad. It’s nice to reward people for giving you a good time… I just feel bad for people wo have customers who don’t value them very much or who say, ‘If you don’t do this I’m not going to tip you.”

For Harrigfeld, the answer may lie in adapting tipping culture. She’s fought for a tip pool at the Boise restaurant she bartends from, which would take the responsibility off individual servers and provide agency to create a safer culture as a whole. While it was met with concern by veteran service workers who worried about losing tip money and ultimately not implemented, Harrigfeld said she believes this system holds patrons accountable.

Harrigfeld has also done her own extensive research into tipping culture and its connections to harassment toward servers. She also believes that a subminimum wage perpetuates the issues tipping creates.

For owners and managers who would like to do more, Chris Davis of the Women’s and Children’s Alliance also encouraged restaurant owners and managers to contact the Women’s and Children’s Alliance for regular education, training, and response techniques.

Other Boiseans are also providing resources to help combat sexual harassment.

Matt Pipkin has created a platform specifically targeted to business and event leaders who want to address sexual assault within their industries and organizations, create meaningful policies to mitigate it from happening, and tools for responding to harassment and sexual violence. Pipkin founded WeVow in 2018, after he learned of an experience his wife had at a work function, where she had no clue how to respond.

That confusion, Pipkin said, unfortunately isn’t all that uncommon.

“I’ve seen that lots of organizations have sexual harassment policies and all that stuff, but no one cares about that stuff,” Pipkin said. “It’s not part of the culture necessarily, and if it’s not part of the culture, who’s going to care?”

Pipkin, who also founded and runs a nonprofit that helps sexual assault victims find counseling support called Speak Your Silence, added that the restaurant industry can be a breeding ground for sexual violence because the risks are higher with a heavy prevalence of alcohol.

With the proper tools and a strong commitment, Pipkin said he has seen restaurant owners and managers prove they are committed to stopping sexual harassment in their establishments.

“If you clearly communicate and then demonstrate that you value your people and then back it up when and if things happen, I think that’s the true prevention,” Pipkin said.

Davis agreed. Not doing so, she added, could be detrimental.

“It really starts from the top down to create that environment of safety… The long-term effects of people being degrading and mistreated – I don’t think people really truly understand that,” Davis said. “It’s like you’re being treated like a commodity.”

Samantha Stetzer is a Midwestern transplant in the Treasure Valley. She is a freelance reporter with experience covering anything from the country fair to political speeches to community legends. Her work has been featured in numerous publications across the U.S.