Story by Lex Nelson

The results are in: July 2021 was the hottest month on record in Boise according to the National Weather Service. Boise Dev reported the month’s average temperature was 83.8° F (6.5° F above normal) and as of Aug. 1, the mercury hadn’t dipped below 60° F in 44 days. For Southern Idaho’s farmers and ranchers, the heat has been a challenge — stunting the growth of crops, reducing the forage for animals, and making farm work more dangerous.

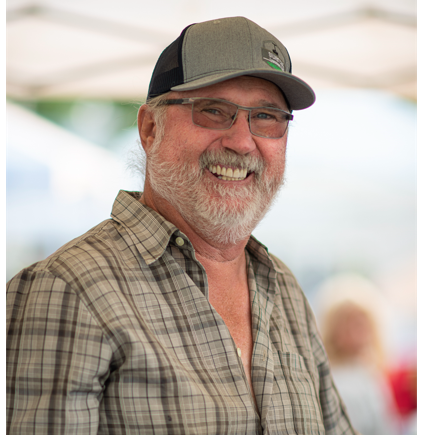

“So far it has been the windiest spring and the hottest summer that I’ve experienced in 30 years, and it has taken a toll on some crops and it’s going to affect the bottom line,” said farmer Lee Rice.

Rice runs Rice Family Farms, two five-acre parcels in Nampa that boast six acres of intensely cultivated warm-season fruits and vegetables, potatoes, and onions. For him, the cold, windy spring was almost as ruthless as the summer heat.

Rice lost his first potential crop of tomatoes and watermelon this spring to “blossom drop” caused by the late chill. (Blossom drop is a stress response to extreme temperatures that forces plants to drop their flowers before they can set fruit.) Then this summer, he lost two more sets of tomato blooms to blossom drop, this time from the opposite extreme.

“We don’t have a tomato crop because of [the heat],” he said. “The blooms all burned off.”

Overall, Rice expects to harvest about 85-90% fewer tomatoes this summer than he would in a typical year. That loss will cut 10-15% out of his gross sales, which rely on heirloom tomato sales to the Boise Co-op and Whole Foods, as well as retail sales of roma and canning tomatoes.

At Ohana No-Till Farm in Meridian, farmer Steve Spiteri is experiencing similar tomato troubles. In the past, tomatoes have been one of his farm’s specialties along with leafy greens, but this year the heat has put pressure on both delicate crops.

“Oh my god, we’re getting crushed,” Spiteri said, referring to his tomatoes, which have suffered badly from blossom drop. Later, he added, “We’re having a hard time keeping enough water on [the salad greens and spinach] to keep it from turning bitter and straight out dying.”

It has also been tough for Spiteri and his fellow farmers at Ohana to eke out multiple harvests of greens.

“Normally we take a cut and let it grow back. Now we cut and it will bolt or die. Production has gone way down and been a lot more trouble,” he said.

The greens humans eat aren’t the only ones affected by heat. Tim Brown of Brown’s Buffalo Ranch in Nyssa, Oregon, reports that the grass his 500 animals feed on is growing more slowly this summer. That makes grazing a challenge, especially when his animals are already inclined to let their stomachs go empty.

“When it’s super hot they’re just not out eating. They’re basically like we are — you kind of eat a little bit more when it’s in the 70s and 80s compared to 100-plus. So this year we’ll wean off smaller calves, probably, because of the heat,” he said.

Brown doesn’t expect a big impact on his operation’s bottom line, but said things could “be really ugly” if temperatures don’t drop this winter.

On top of the heat, smoke from the Bootleg Fire in Oregon and the Beckwourth Fire in California poured into Southern Idaho throughout July and continues to fill the Treasure Valley in August. It may be impacting yields, too.

“It seems like my onions are taking a long time to mature. Normally they wrap up pretty quick and bend over, you know, [but] onions are really daylight sensitive,” Rice said. “I’m wondering if the smoke is blocking enough of the light to mess them up a little bit, delay them a little bit. It’s either that or thrips [one of several destructive bugs that thrives in high heat].”

The heat and the smoke create tough conditions for farmers as well as their crops. Rice estimates his team has spent “10-15% more time just moving water” this summer than cooler years past. Both he and Brown have the same mantra of “start early, finish early” to avoid heat exhaustion, and Spiteri encourages his fellow farmers to take breaks and drink water.

The most these farmers can do, it seems, is keep hustling and look on the bright side. Several pointed to crops like peppers, blackberries, and cucumbers that thrive in higher temperatures. Others noted that their crews have worked in hot, smoky, conditions before. Rice is even half-hoping for an October crop of tomatoes, if high temperatures continue.

“That’s kind of an iffy thing,” he said, chuckling a bit, “I don’t know if I want the weather to stay hot enough that long.”