By Carissa Wolf

Photos by Guy Hand

The Covid-19 pandemic pushed a global pause button that shuttered businesses and stopped the world in its tracks. But inside cocooned Boise eateries on quiet, vacant streets, a buzz of activity swirled as workers and restauranteurs prepared for an unwitting metamorphosis.

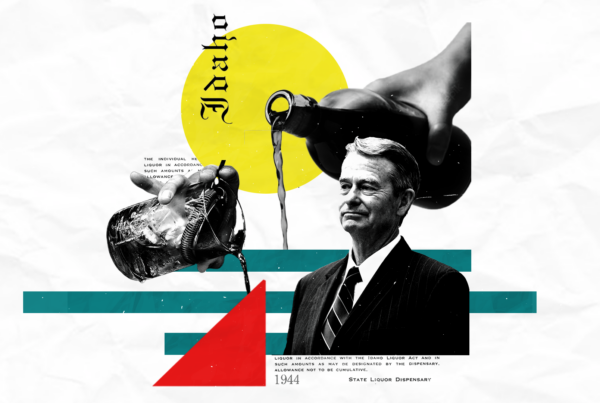

The days between the announcement of Idaho Gov. Brad Little’s stay-at-home orders on March 25 and the first phase of the Idaho reopening plan on May 1, a wash of transformation, rebuilding and reimagining quietly shifted the Boise dining scene toward a new life.

Scores of passionate restaurant workers and operators stayed on the job although the jobs looked very different and the new restaurant duties of the Covid-19 era demanded as much heart as skill and sometimes came without a paycheck.

“I was surprised by the number of people who did not quit,” says Dave Krick, owner of Bittercreek Ale House, Red Feather Lounge and Diablo and Sons, three restaurants that sit on Boise’s usually bustling and famed “Restaurant Row,” along downtown’s Eighth Street.

“We have people that never quit,” Krick says. And the many restaurant workers that have returned to jobs in recent weeks did so without a lot of financial incentive, he notes.

A drive to keep Boise’s dining institutions and the people that are a part of them safe and strong defined the nearly two-month long closure that left establishments mostly empty and doors closed except for occasional delivery and to-go orders.

Customers stayed home but the hard work never went away. Cooks and servers pivoted to adapt to the changes delivery and to-go orders demanded; veterans in hospitality became a unified voice for public safety and small business interests; city leaders and restaurant owners reimagined city streets and beloved chefs became a lifeline.

The most visible role that restaurant and bar operators reimagined for themselves came during the early days of the pandemic when nearly 100 owners from around the state signed on to a letter asking Gov. Little to order bars and restaurants to close and provide unemployment benefits to laid-off workers. Citing public health and economic viability concerns, the signers told the governor a shutdown was a matter of survival.

Many of the restaurant owners that signed that letter formed FARE Idaho (Food, Agriculture, Restaurant and Beverage Establishment), an alliance of small and independent farmers, producers, retailers and bar and restaurants that advance and advocate for the food industry and its workers. Among the FARE agenda: finding viable solutions to guide the industry through the Covid recovery. Members meet regularly, share ideas and talk about how to make sure new safety protocols work.

“There is no cookie cutter model. You have to tailor (changed),” FARE member and restaurant owner Chad Johnson says.

What works at Johnson’s tiki bar, the Reef, may not work at his sports pub, Legends, he says.

In recent weeks, FARE members have worked with Boise City and Ada County Highway District to reimagine the downtown Boise cityscape into a community of “streeteries,” where streets and parking spaces shut down à la European style to allow dining, pedestrians and social distancing to fill the streets. Boise’s Eighth Street between Idaho and Bannock Streets became the latest example of how our dining scene can be permanently reimagined when the city closed the street to cars at the beginning of June.

FARE members also help each other deal with practical matters customers may never think about, like what to do when paper bags become the new toilet paper and food supplies get cut off. They’re also thinking about the community.

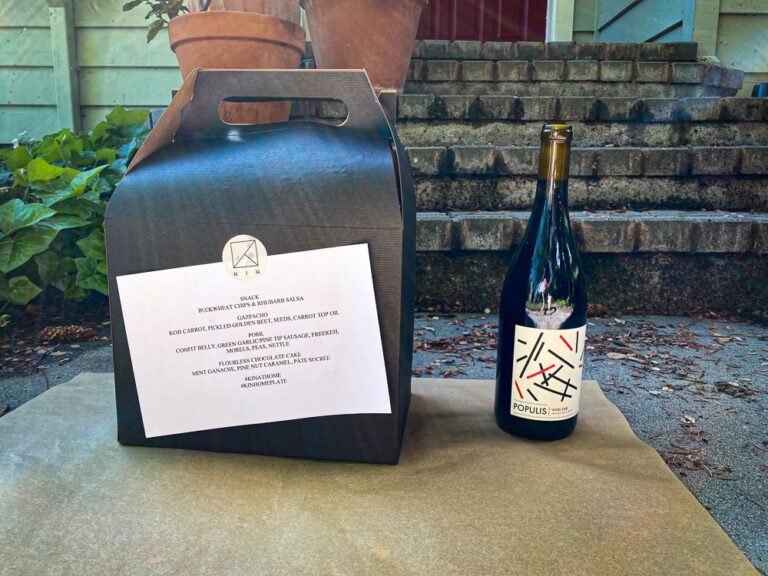

Remi McManus and business partner, Kris Komori were slated to open their latest carnation, KIN at the corner of 9th and Main Streets and looked forward to opening the space once occupied by the Idaho Shakespeare Festival to live performances. Then the pandemic hit.

“COVID changed everything. I’m not sure it’s an advantage or disadvantage that we had not opened yet. We had to lay off 20 employees.”

Still, McManus says, “We’ve done a lot of things since the shutdown.”

The KIN team reimagined what dinner could look like and began offering gourmet dinner kits that come complete with video cooking classes and evening musical entertainment. They also began to reimagine a Boise food scene where everyone could have access to safe, healthy food.

The duo that earned James Beard Foundation nods for their elevated farm to table approach to local flavors at the late State and Lemp teamed up with Krick, the Boise Co-Op, Treefort, Music Festival and others to create City of Good to deliver meals and meal kits to vulnerable populations and those affected by the Covid fallout. City of Good projects include partnering with the Boise School District and local restaurants to raise funds and tap into food donations to get food where it’s needed most.

“We wanted to give back to the community,” McManus says.

In the days that images of wasted meat and produce, piles of unused potatoes and tankers dumping milk made the news, local restaurants reimagined a different future for what could have become discarded food. The owners of Bar Gernika, Manfred’s and other eateries began delivering unused food to employees and sought donations to keep the deliveries going.

“A little bit went a long way” says Manfred’s co-owner, Bart Kline.

When they saw it wasn’t just restaurant workers that felt the pinch of unemployment and delayed relief payments, they expanded their reach to serve artists and musicians.

“It was the right thing to do,” Kline says.