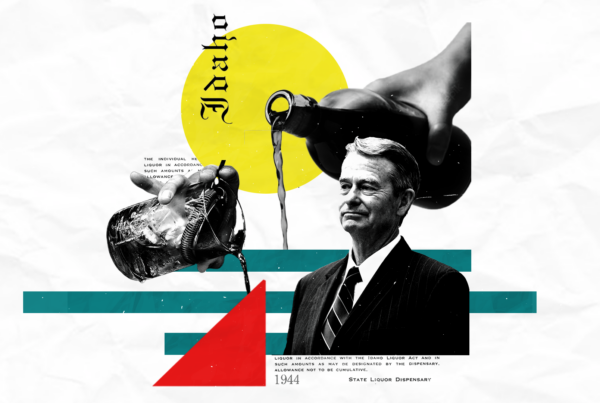

Story by Lex Nelson; Photography by Claire Everson

Boise restaurant owner Kasey Montgomery is what you might call a national restaurant chain expatriate. He spent years working for Matador and the 14-brand restaurant group Restaurants Unlimited before opening his first hyper-local concept, Juniper, in 2017.

Juniper’s website lists more than 50 regional suppliers, including farmers, distilleries, and wineries. But when asked if the chains he used to work for ever bought local, Montgomery scoffed.

“It was never something that was ever even talked about,” he said.

Why is that? According to Montogmery and fellow Boise locavores/chain expatriates Cameron Lumsden (co-owner of Fork and Alavita) and David Rex (co-owner of The Wylder and Certified Kitchen + Bakery), it often comes down to cold, hard cash.

Money, Money, Money

“Everybody wants to serve [food that’s] organic, free-range, locally-sourced, harvested by local people — everyone wants to do that! But, I don’t know, most people can’t always buy a $17 organic mixed-greens salad with heirloom carrots,” said Rex, who worked for Upward Projects, LGO Hospitality, and Lettuce Entertain You before opening The Wylder. “It’s not always in the budget, especially right now.”

It’s true that local food from small farmers is often more expensive than imported produce — a problem that plagues small and large restaurants alike. But concerns about scaring off customers with high prices are just one piece of the deterrence puzzle. Sourcing locally also raises internal food costs, which can require sacrificing profits. Montgomery knows this all too well.

“At Juniper we run a really high food cost. And it’s a commitment. You have to go, ‘This is what we’re doing because we believe in the quality, in supporting the local economy, and in all that goes with that. But it’s not easy. When the going gets tough it’s a lot easier to bail and say, ‘Okay, let’s just get a few of these things and call it good,’” he said.

National chains bite that bullet less often, which Montgomery said may be because they have access to discounted supply chains out of reach for one-off restaurants.

“When you get into those multiple locations, obviously part of the benefit of that is buying power,” Montgomery explained. “So the more you work with, you know, the bigger distributors, the more they’ll give you breaks on ordering for everybody. You commit to buying X amount of whatever it is, and get a [cost] break. So they don’t care about local, they care about that dollar savings.”

A Quality Problem

Money isn’t the only thing chain and individual restaurants consider when debating where to buy produce: quality is also a big player.

“First and foremost we focus on the quality. Is the quality good? Because if you don’t have that, it doesn’t matter what you’re serving,” David Rex said.

The Wylder sources much of its wheat from Utah, and brings in organic plum tomatoes from California for its pizza sauce. Rex noted that while he’d love to source tomatoes locally, Idaho’s climate just isn’t suitable for growing large quantities of tasty, cold-sensitive produce in the volume he needs year-round. Montgomery follows the same ethos at his other restaurant, Red Bench Pizza.

“We want quality food. I don’t care if it comes from Italy, or Idaho, or Utah. The focus is that we want to have as high-quality of ingredients on our pizza as possible,” he said.

The word “quality” has a lot of meanings, but it comes down to three things: taste, consistency, and safety. It’s difficult for a local farm with a small footprint and seasonal limitations to meet all three requirements up to a chain’s standards — particularly the latter.

Why Size Matters

In an interview with Harvard Business Review, “All Business Is Local” author and professor John Quelch said chains often stick with national suppliers because it’s more challenging to monitor and quality-control dozens of short supply chains than four or five long ones.

“Local sourcing adds complexity, increases risk and fragments the supply chain,” he said. “Even if you have a standard quality control procedure for all of your sources, you’re not going to be able to monitor them on-site at every location. You’re going to have to put your trust in the suppliers to live up to the expectations laid down in the quality control guidelines.”

Lumsden saw these issues first-hand while working as a manager at P.F. Chang’s, an operating partner at Fleming’s Prime Steakhouse & Wine Bar, and a joint venture partner at Blue Coral Seafood in the 1990s and 2000s.

“Sourcing locally would make it challenging for multi-unit restaurants primarily due to consistency of product, availability, demand for high quantities, transportation, as well as pricing,” Lumsden said. “… The chains I worked with did not specifically procure local ingredients primarily [due] to them being multi-unit in different states across the country.”

Instead, he noted, those chains prioritized forming relationships only with the farmers, ranchers, and fishermen who supplied key products like beef and seafood.

Is Change Possible?

Asked about the future, Montgomery said that motivation for chains to buy local “would definitely have to come from the public.” He added, “That goes back to the public being educated on what they’re eating, the difference [between local and imported food], and why it’s important.”

At Juniper, Montgomery’s team works hard to provide that education to diners. That includes explaining where their ingredients come from, why local dishes have a higher price tag, and why the sustainability of, say, local eggs, really matters.

“You hope that [after eating the local egg] they’re going, ‘Wow, that was really good!’ But we also need to get in front of them and say, ‘These are Western Sunset Farms eggs, they’re local eggs, and you’re supporting that,’ so that they know and get it. Then next time they make a decision, that will be part of what they base the decision on,” he said.

But even with these efforts, at the end of the day restaurants are still forced to walk a profit margin tightrope that has only narrowed during the Coronavirus pandemic.

“You obviously want to support the community whenever you can,” Rex said. “But you also want to stay in business and make sure [your employees and customers] can pay their rent.”